My journey through the decompilation and remaster of Star Wars Episode I Racer - 12 Feb 2025

If you are interested about the project, you can go to this page instead.

When I was younger, I use to play the old Star Wars games such as Rogue Squadron and Star

Wars Racer. I've always enjoyed these games, and at some point I decided I wanted to

remaster Star Wars Racer (SWE1R or SWR), because the game was great but the graphics were

getting dated. At that time, it was just a childhood dream that I kept in the back of my head. I just

thought it would be cool to do it but never started it.

I joined the community in 2019, after playing the full campaign again. This is when I

discovered multiplayer and community tournaments being held regularly. I've met some great people, and

this reinforced my idea to do a remaster for the game one day.

Fast forward a couple of years and I'm a software engineer student. I'm learning a lot of low level,

mostly C, but also specialize in 3D graphics, which I particularly enjoy.

During one of my year, I met a younger student that was into reverse engineering and low

level

programming talking about how he helped in the decompilation and recompilation of Zelda Ocarina of time.

I thought that if he was able to do it being younger than me, I had no excuses not starting

my own project. I asked him some advices about how he did it and what tools he used / what

was the process. At that time in my studies I had more free time than before,

so I started the decompilation repository for the game the 28 January 2023, just over two

years from now.

My overall plan was:

- Understand the game well enough to replace the original renderer by our own

- Make pretty modern graphics with Physically based rendering and Image based lighting (I've learned about it and it was a perfect match for this project).

- Replace the models with better quality assets and textures. I only have very basic knowledge of Blender but there are some better artists in the community whom I could help, by making an interface to the game rendering somehow.

I had the technical abilities to do it, and knew how to do OpenGL and shaders. I had, however, no competency in Reverse Engineering and decompilation, and only a very basic understanding of assembly. Well, if my friend learned it, what stops me from learning it too ?

I decided more clearly what the decompilation project should be, after talking to friends. On the Legal aspect, I see that reverse engineering is a grey area as long as no harm is done. I decided to not decompile the whole game and not try for matching decompilation since this could be enabling piracy. On the other hand, the modding scene for Star Wars BattleFront 2 (2005 edition) was really dynamic and flourishing, and they were providing great value for players. That's what I wanted to do for Star Wars Racer, even though the community is much smaller.

Decompilation and technical part

Starting the project

Looking at the community efforts, there was already some work done on decompilation and porting such as openswe1r, swe1r-re from JayFoxRox, and swe1r-decomp from Galeforce. The first step of the plan would be to aggregate all the work done here and there into a big decompilation project, which would help me go faster, help others to reduce the duplication of work, and be an easier introduction to reverse engineering for me. I would thus base my work from where JayFoxRox stopped, the previous guy working on decompilation, and merge informations from the other sources. He had already left about 4 years ago at the time, but left some valuable notes about various function of the game. This was perfect for me ! There was already some work done that I could compare on Ghidra and see the back in forth between assembly and the C code equivalent he made. Similarly, LightningPirate had a private repository being untouched for about 2 years where he had notes, which he happily shared to me. Starting from these notes was really helpful since I didn't have to start from scratch and learn everything at once.

For the reverse engineer part, I started with the basics such as dumping all the strings to see if anything was popping out. Indeed, some strings already give valuable bits of information

// Reference to rdroid

D:\devel.QA5\pc_gnome\SpecPlat\rdroid_gnome\Source\elfCallback.c

elfControl_ReplaceMapping(cid, fncStr, whichOne, bAnalogCapture, sign, lastBinding)

elfControl_ReplaceMapping(cid, TXT_ROLL_RIGHT, whichOne, 1, -sign, lastBinding)

elfControl_ReplaceMapping(cid, fncStr, whichOne, bAnalogCapture, 0, controllerBinding)

D:\devel.QA5\pc_gnome\SpecPlat\rdroid_gnome\Source\elfControl.c

elfSaveLoad_SaveThisGameStruct()

D:\devel.QA5\pc_gnome\SpecPlat\rdroid_gnome\Source\elfSaveLoad.c

// Most importantly, mention of Jones3D and tVBuffer structure

D:\devel.QA5\pc_gnome\SpecPlat\rdroid_gnome\Jones3D\Libs\Std\Win95\stdDisplay.c

D:\devel.QA5\pc_gnome\SpecPlat\rdroid_gnome\Jones3D\Libs\Std\General\stdColor.c

D:\devel.QA5\pc_gnome\SpecPlat\rdroid_gnome\Jones3D\Libs\Std\General\stdBmp.c

Unable to allocate memory for new tVBuffer

wKernelJones3D

Setting hanger state to HANGAR_STATE_MAIN_MENU

Setting hanger state to HANGAR_STATE_SELECT_PLANET

Setting hanger state to HANGAR_STATE_SELECT_TRACK

Setting hanger state to HANGAR_STATE_DONTCARE

// CLSID for Windows IUnknown Interface for a3dapi.dll, D3D, DInput, Dplay

// Also this joke that got trimmed by the compilation process. We'll never know the punchline

Stop me if you've heard this one.

A jawa and ewok walk into a bar.

The ewok says 'Hey bartender, get me a--' but stops, amazed,

when the jawa grabs his cloak and starts pointing at the<truncated here>

Some strings found in the game executable

Getting help from similar projects

Appart from In-Game strings easily recognizable, some debug path that should not have been there spiked my curiosity. Google would point to OpenJKDF2, a very similar project than the one I was attempting, but already much more advanced. It turns out Jedi Knight Dark Forces 2 has some similar engine library function than what we can find in SWR. Let's just try to match every JKDF2 function with ours ! Speaking with the members of the JKDF2 community, one member, Urgon informed me about the Jones3D being part of the game Indiana Jones and the Infernal Machine released by LucasArt for N64. He was working on a decompilation for the later and provided me with additionnal informations about the engine. Notice that the game was released for N64, and that Star Wars Racer was also released on both PC and N64.

The math library are almost identical for the 3 games, which can be explained by LucasArt developping so much games that engine reuse would be common practice, like in many studios at the time.

Let's take a look at some common functions in both engines.

// Example of output by Ghidra after having defined some types

void __cdecl rdMatrix_BuildRotate34(rdMatrix34 *out,rdVector3 *rot)

{

rdVector3 *prVar1;

float local_1c;

float local_18;

float local_14;

float local_10;

float local_c [3];

prVar1 = rot;

stdMath_SinCosFast(rot->x,(float *)&rot,&local_1c);

stdMath_SinCosFast(prVar1->y,&local_14,&local_10);

stdMath_SinCosFast(prVar1->z,&local_18,local_c);

(out->rvec).x = -(local_18 * local_14) * (float)rot + local_c[0] * local_10;

(out->rvec).y = local_18 * local_10 * (float)rot + local_c[0] * local_14;

(out->rvec).z = -local_18 * local_1c;

(out->lvec).x = -local_14 * local_1c;

(out->lvec).y = local_10 * local_1c;

(out->lvec).z = (float)rot;

(out->uvec).x = local_c[0] * local_14 * (float)rot + local_18 * local_10;

(out->uvec).y = -(float)rot * local_c[0] * local_10 + local_18 * local_14;

(out->uvec).z = local_c[0] * local_1c;

(out->scale).x = 0.0;

(out->scale).y = 0.0;

(out->scale).z = 0.0;

return;

}

Here is an example of a mostly pure function (No global variables, almost no calls to sub functions). Its pretty easy to understand what is going on after having defined the matrix type and looked at how the data flows. In most cases though, the function references unknown global variables and call unknown functions, and we have to go down the function calls in hope of finding more understandable structures.

// Example of the system API to be more portable

typedef struct HostServices

{

uint32_t some_float;

int (*messagePrint)(const char *, ...); // 0x4

int (*statusPrint)(const char *, ...); // 0x8

int (*warningPrint)(const char *, ...); // 0xc

int (*errorPrint)(const char *, ...); // 0x10

int (*debugPrint)(const char *, ...); // 0x14

void (*assert)(const char *, const char *, int); // 0x18

uint32_t unk; // 1c

void *(*alloc)(unsigned int); // 0x20

void (*free)(void *); // 0x24

void *(*realloc)(void *, unsigned int); // 0x28

uint32_t (*getTimerTick)(); // 0x2c

stdFile_t (*fileOpen)(const char *, const char *); // 0x30

int (*fileClose)(stdFile_t); // 0x34

size_t (*fileRead)(stdFile_t, void *, size_t); // 0x38

char *(*fileGets)(stdFile_t, char *, size_t); // 0x3c

size_t (*fileWrite)(stdFile_t, void *, size_t); // 0x40

int (*feof)(stdFile_t); // 0x44

int (*ftell)(stdFile_t); // 0x48

int (*fseek)(stdFile_t, int, int); // 0x4c

int (*fileSize)(stdFile_t); // 0x50

int (*filePrintf)(stdFile_t, const char *, ...); // 0x54

wchar_t *(*fileGetws)(stdFile_t, wchar_t *, size_t); // 0x58

void *(*allocHandle)(size_t); // 0x5c

void (*freeHandle)(void *); // 0x60

void *(*reallocHandle)(void *, size_t); // 0x64

uint32_t (*lockHandle)(uint32_t); // 0x68

void (*unlockHandle)(uint32_t); // 0x6c

} HostServices;

Here is another interesting example. In order to be as portable as possible, most calls from the game go through this "API". In order to support new platforms, developpers simply modify the callbacks in the initializer function for this structure. Since assets files are in a custom format as binary blobs, they can be embedded in a cartridge for N64 or stay as files to be read for windows and mac, and the familly of file reading function can be swapped without issues. The debug prints in the release

With the merging going at a good pace, some pure functions would already be decompiled, which help understand more complex functions, and so on. This provide a compounding effect that makes decompilation faster and faster (As well as my skills improving in understanding assembly and decompilation).

Learning the old windows api the hacker's way

The next easier step for me to understand the game would be to find documentation about some of the game's api. Mainly Direct3D, DirectInput and Aureal3D, for graphics and sound. I've noticed a lot of unknown pointers that would get dereferenced with offset and called afterward.

// Some weird looking variables

iVar2 = (**(code **)(*local_5c0 + 0x2c))();

// Some binary blob being passed to one of the function

binaryBlobData = 82 e6 44 59 2e c9 cf 11 bf c7 44 45 53 54 00 00 // in reality, just an address to those bytes

iVar2 = (**(code **)*puVar6)(puVar6,&binaryBlobData);

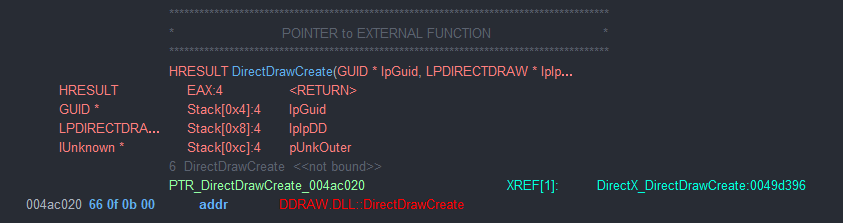

This looks like a virtual table for something, but I don't know why, nor what are the functions. DirectDraw is helping here since the initialization function has been dynamically linked. By working from there I think I get a better chance at cracking this mystery. Ghidra can give me this information:

Ghidra informations about an external function

By reading the Microsoft Documentation about this function, we can get the arguments type. I couldn't get the exact structure definitions on the Microsoft documentation though, so I had to find it elsewhere. Looking on the internet for these definitions, I found the ddraw.h header in the apitrace github repository. I could then adapt the header for the version the game uses (DirectDraw4). The process is similar for the other dlls. For example, I found the dinput definitions on the wine repository.

By merging these definitions with the decompilation database, this made me learn about GUID, QueryInterface(), CoCreateInstance() and the IUnknown interface model. I've always coded C on Linux so this was a very convoluted way to learn how windows worked back in the days.

The end of low hanging fruits

Things were going well. The base libraries and the main interfaces have been found and matched with other projects, and I've become more comfortable reading Ghidra pseudo-C, and navigating between cross-references, data and functions. One of the last easy win would be to find the parsing functions for the config files the games reads and writes.

The decompilation of the IO of config files and assets would slightly help understand the inner working of the game, but not much more. Some config files for mappings, sounds, visual quality are parsed by the game into global variables that can be cross referenced with functions using them. The assets parsing however would prove much more difficult to understand than the config files. All the assets of the game are parsed from 4 binary blobs named modelblock, splineblock, spriteblock and textureblock. The understanding of these files data, both from external static analysis and analysis from looking at the parsing code would be essential in unlocking the custom format of the 3D models defined in it. This could enable manipulation of in-game assets via decompression-modification-recompression in a tool like blender, as long as the format matches what the game expect. These file and their format would remain a mystery for a lot of time, since their structure were not like the other games.

The following months would be slow decompilation, scraping every bit we can so that we can make sense of what is going on where. On ghidra, that would be either trying to find a small function that is sufficiently independent to understand on its own, or find references between global data and functions to infer its use and meaning. Sometimes, understanding how a global variable interacted with the code could unlock larger comprehension of the game, and sometimes I would just understand one or two random function each evening for days. Some systems would always be referenced such as the game object management system, while others much less, which would push our knowledge boundary into the game's internal logic. This effort was starting to be useful for future modding endeavours. On the other hand, the decompilation got more tedious, and very time consuming. I would keep decompiling regularly with the determination that this would enable something bigger to be built on top of it, but the time horizon became much more incertain. My 4-6 naive estimate has already been reached, and I had no idea how much efforts it would take for a breakthrough.

A new hope

Some work put in evidence that the game uses a single id for each asset (model, sprite, texture), that is used to fetch the corresponding data by reading the asset blocks. We were slowly matching ids to their corresponding model, but luckily the enum got leaked in the release of the Nintendo Switch version, with the source files available next to the data blocks. This was a nice time saver.

In November 2023, eleven months after I started this project, Aphex shared custom code he had to parse the structure of the binary blocks. This gold mine of knowledge helped us tremendously in understanding both the static data of the binary blobs of the game, as well as the parsing logic inside the game. He was working on it for a long time and cross referenced multiple versions of the game to check his script was working properly. He is the one that knows most about the game assets, and was the first to decompress, modify and recompress a binary asset block into the game, which was an important milestone for this project.

An HD part by LeadPhalanx, inserted in the modelBlock by Aphex's tool

The textures have different format with or without palette and transparency. The models have

hierarchy informations and different node types (with or without children or transform).

Some data that we couldn't make sense of at first, was discovered to be N64 display

list for GSP in the F3DEX_GBI_2 format, a microcode used to control the rendering. If you

are interested, here is a link to the N64

programming Manual section and the N64

GSP Function reference.

This made us discover some hardcoded limits of the game that would be very hard to fix.

For example, there is a fixed number of triangles the game can show at once, and a limited

number and total byte size for textures. To circumvent these limits, having a separate

renderer is much easier and powerful than trying to patch every part of the game that

reference them.

This is were the fun begins

Our decompilation progress marching forward one function at a time, we were starting to discuss how much more we needed to decompile, in order to start doing the things I wanted to do in the first place. Do we really need to decompile the code of the menus and button callbacks or the physical simulation part ?

With math function, camera functions, 3D functions, system functions, our understanding was good enough that the 13th mars 2024, another community member named tilman managed to hook and replace enough functions to run imgui and an opengl api replacement, proving that we had enough decompilation already to start replacing graphics. With this proof of concept working, most of my time from this point onward went into improving the renderer replacement. After a bit more than one year of slow and monotonous decompilation, the fun part of building the gltf renderer was upon me ! I wanted support for renderDoc since its a powerful tool that would greatly help. Unfortunately, the replacement was done with immediate rendering to be as close as possible to the original one. Tilman and I started to swap the rendering for immediate openGL to the more modern api, and we had renderDoc support just like that !

The following months would be spent finding ways to hook functions and load the renderer in a simple and efficient manner. I tried patching the game statically but didn't really like the solution. It was messy and inconvenient to use. I tried dynamic patching, which was already a bit better. One would run the patcher, which would run the game and stop it, modify the main function, load the mod dll which would hook all interesting functions, then resume the execution of the main thread. What I liked was that the loader could do more, like provide a UI, some control when loading multiple mods, and more. Galeforce, who was working on decompilation as well, was developping another mod loader in parallel (annodue), to add speedrunning features. I didn't really want to compete with him, and realized that my loader would need much more work to be on par with his. I finally settled for a simple dll injection that would hook the functions into the original game. The final user would just have to unzip an archive an run the original game to enjoy mods. This was the simplest solution for me and the final user, and compiling to a dll would help when I would finally integrate my mod to annodue.

The final step of this project would be implementing the gltf specification with the help of the gltf sample renderer and the gltf sample models, which are very high quality source of information. I had to be careful about some models since pods are animated from the game's data (When turning, when breaking an engine, going up and down slopes). GLTF files can be exported by Blender, have a parser already available (tinygltf.h), have PBR capabilites, and is a very simple format to render, which checks more boxes than I had. I set a test scene to be rendered inside the game, and added support for features until I had all that interested me. I even added animations since I knew that could be a cool feature for artists to use.

First release

I've done the first release of the mod on February 6 2025, 2 years after the beginning of

this project.

What I thought would be a 4-6 month project took much longer than expected, and the journey

to get there was a great experience. The beginning of the project was exciting, followed by

months of boring decompilation, until Aphex and Tilman breakthrough, which unlocked our

ability to develop with our own code. Galeforce and LightningPirate were always here to

answer my questions, being amongst the oldest members still active. I could not have done it without

each of them.

When starting this project, I didn't have much self-confidence, and only ever did school project that would re-invent the wheel over and over again. I wanted to complete the hardest possible project I could think of, and I believe I finally succeeded in making my childhood dream a reality. I've gained the habit of regularly coding on the evening and I find it to be a greatly satisfying activity. I'm much more confident in my ability to create and build things and I have lots of ideas for future projects. If I had an advice to my past self it would be to go for it now and think about it later.

I've always wanted to build tools to enable artists and this project is a good example of that. In the community, Leadphalanx working on High Resolution pods and DigitalUnity who made the lego mini pods are already showing what can be done with this new tool. I wish one day we'll have remastered all the tracks and pods, but as community members, I think we are already doing an amazing work.

Epilogue

While writing these two articles, LightningPirate shared his opinion on my work, which deeply touched me. Here is what he has to say:

LightingPirate: "I don't want to tell you how to do your personal article but as a testimony I'd like to

say...

Before you came along the modding scene was just a handful of guys working in isolation on our own

little projects with little crossover. None of us could really see the entire picture. Because of that,

the knowledge was all over the place. So when you came and synthesized it all and shared your vision,

that's when it finally felt like a group effort, all amounting to something impactful and benefiting all

modders. It is a high value skill to be able to understand and manage multiple projects like this, in

different languages/contexts, and merge them into one cohesive vision. That's something I would brag

about if I were you :HappyFud:".

Indeed, I don't think I'm very good at selling myself. I am very grateful I could share my vision for this game with others, and that we could cooperate into creating something we can share with the larger community of Star Wars Racer players. I hope my work will speak for itself and that people will like playing this prettier version of the game.